Mental illness in prison

Report by Chris Reid and Gaia Giampietro

- Psychiatric disorders are overrepresented among prisoners compared to the general population, both globally and in the UK (Fazel & Seewald, 2012; Tyler et al., 2019).

- Current research indicates that, globally, 1 in 7 prisoners (14%) are diagnosed with psychosis or depression – these figures have been relatively stable over the past 30 years (Fazel et al., 2016).

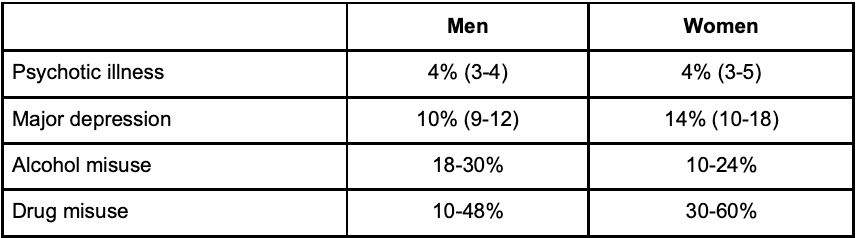

Prevalence of different psychiatric diagnoses in adult prisoners based on systematic review of 23,000 prisoners (Fazel et al., 2012)

- In the UK, specifically, comprehensive figures regarding mental illness prevalence have not been conducted since 1997 when data was collected by the ONS

- However, the data gathered is still valuable:

- The study also highlights distinct profiles between remand and sentenced prisoners, i.e. remand prisoners generally have much worse mental health

- Research conducted by Tyler (2019), deemed as one of the largest studies concerning prisoner mental health since 1997, noted that prevalence rates appear to have remained similar, although notes a drastic increase in overall prison population. Some of their findings:

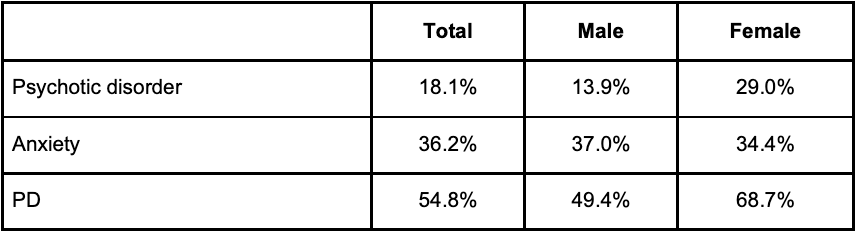

Prevalence of disorders screened positive for on measures (Tyler, 2019)

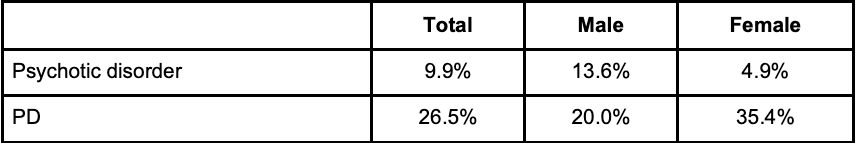

Lifetime diagnoses for participants by gender (Tyler, 2019)

- Furthermore, the study found that 48.8% of participants had reported previous contact with mental health services, either within prison or in their community, whilst 42.2% of participants reported possessing a previous diagnosis of mental illness.

Does prison exacerbate/aggravate symptoms?

- However, evidence regarding change in psychiatric symptoms within the prison environment is complex, and less well-established; nevertheless, it is possible to obtain best guess figures relating to the UK prison population (e.g., Hassan et al., 2011).

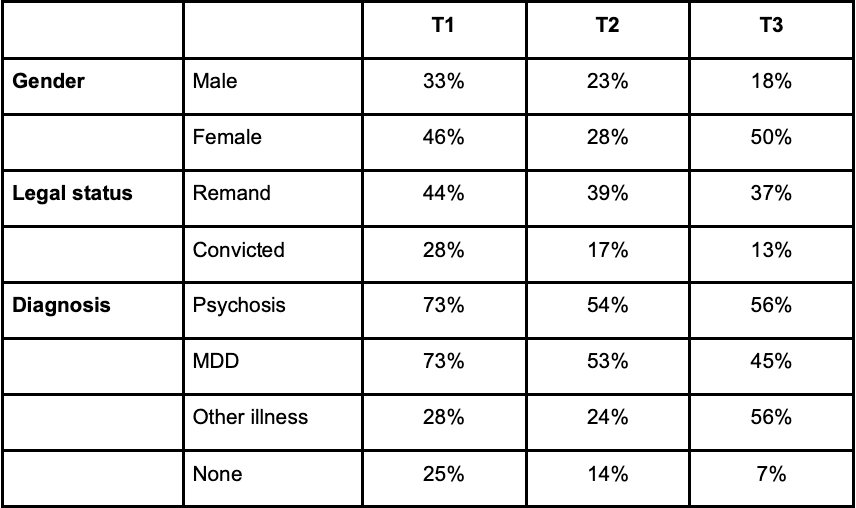

- Research conducted by Hassan et al. (2011) studied rates of psychiatric symptoms in prisoners, measuring these at baseline (T1), 3-5 weeks later (T2), and 7-9 weeks later (T3). Findings reported:

Prevalence of General Health Questionnaire (GHQ) prison caseness (Hassan et al., 2011)

- Therefore, symptoms decreased among men and convicted prisoners, but not among women and remand prisoners (whose symptoms might indeed aggravate). Moreover, symptoms decreased among prisoners with depression, but not among prisoners sufferingfrom any other mental illness (e.g., psychosis).

- Additionally, prisoners have been found to report particularly poor mental health soonbefore release, due to the uncertainty that presents at this time (Lennox et al., 2012).

What happens after release?

- On release, prisoners are often faced with housing issues, with 1/3 of prisoners losing housing after imprisonment, 1/3 of prisoners having no housing following release, and repeat prisoners often becoming homeless upon release (Mills et al., 2013; SEU, 2002).

- Accomodation is part of the seven reducing re-offending pathways (Home Office, 2004); therefore, lack of housing can often lead to reoffending (Meek et al., 2013).

- Additionally, individuals suffering from psychotic disorders present higher risk of recidivism compared to the general population (Fazel & Yu, 2011).

- Homeless and those not in stable housing are overrepresented in British prisons: According to the SPCR, a 2004/05 longitudinal cohort study, 8% of prisoners were homeless before entering custody, however this figure increases to 10% for those sentenced to less than one year. Further, about 7% were in a hostel or temporary accommodation and 17% were in rent-free accommodation(Stewart, 2008; O’Leary, 2013)

- SEU (2002) on Reducing Re-offending by Ex-Prisoners states that:

“Research suggests that stable accommodation can make a difference of over 20 per cent in terms of reduction in reconviction”

However, this research is limited and does not demonstrate causation. - About 37 per cent of all prisoners stated that they would need help finding a place to live when released. Of those offenders who needed help with finding a place to live after custody, 65 per cent were reconvicted within one year of release, compared with 45 per cent of those who did not feel they required help (Ministry of Justice, 2010.

- There is greater need for further research to demonstrate a causal relationship between housing and recidivism (O’Leary, 2013)